The Helmet Creek Patrol Cabin in Kootenay National Park as it appeared this February when the park’s trail crew was dispatched to clear record amounts of snow from the cabin roof and nearby bridges. For more snowy images from Helmet Creek, check out February 20 on Facebook-Kootenay National Park.

Since I started writing this blog back around 2014, I’ve tried to predict when the first high trails in the Rockies would be dry enough to hike. One of my tools is snow pillows—snow survey stations scattered through the Canadian Rockies on the Alberta and B.C. sides of the Great Divide. (For more about snow pillows, see Snowpack in the Canadian Rockies’ high country, Feb 28, 2014.)

The real global warming

One of the myths of global warming is that Canadian ski areas would suffer from a lack of snow. But warmer temperatures don’t mean less snow. When I first came to the Canadian Rockies and worked on the ski patrol at Lake Louise, winters were a lot colder than they are now. And we suffered from sparse snow cover on the slopes.

But in the past decade, temperatures have been noticeably warmer and snowfall has trended well above the longterm average. Meteorologists can explain the phenomenon, but suffice to say, it doesn’t have to be brutally cold to snow. And the more moist weather systems funnelling in from the Pacific, the more snow.

That has been the case over the past six years since I started monitoring snow survey stations in the spring. And this year is one of the snowiest.

Uncertainties of the 2020 season

But spring snow depths are only one factor affecting how early trails will be in shape to hike. A lack of snowfall in late March and April plus above normal temperatures can dry things out fast.

And in this coronavirus year, there is the added uncertainty as to whether national and provincial parks will allow hikers onto the trails. Like ski resort operators staring out their windows at the best spring skiing conditions in recent memory, hikers may only dream of treading high country trails this summer.

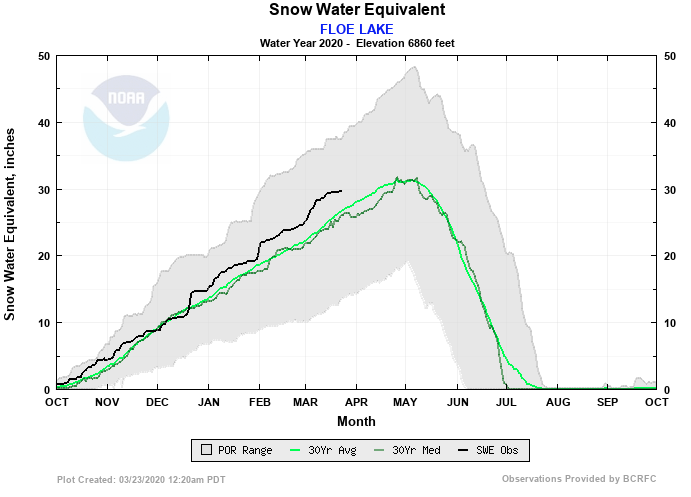

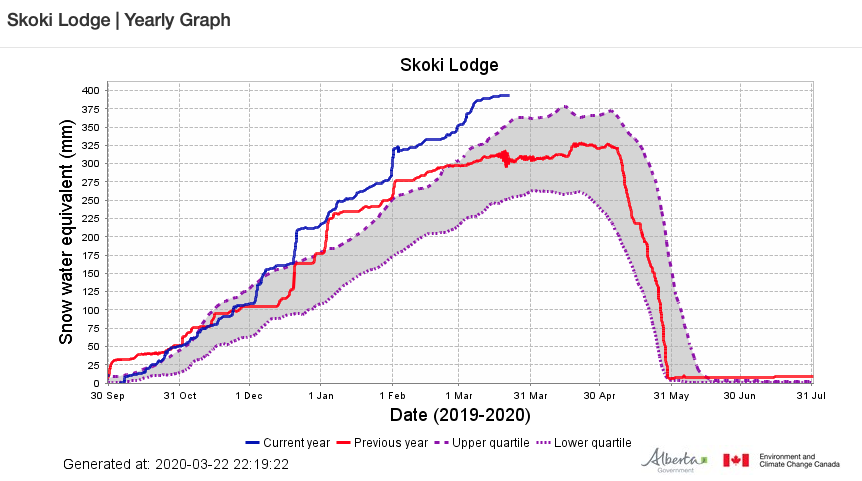

All snow survey stations in the Rockies were registering near record amounts of snow as of late March. Below are just two snapshots of snow depths compared to last year and averages from previous years—Floe Lake in Kootenay National Park and Skoki Lodge in Banff National Park:

0 Comments